But is Banksy exacting payback on our behalf or his? Is pointing to the ridiculousness of the one-percent just so he can join them actually changing anything for the better? Or is it all a show we turn on when there’s a new episode? Something to talk and tweet about while the story’s trending—forgetting to ask the questions that this work should truly provoke from us.

I’ll say this: I just got a Master’s in art history because I believe that artists like Banksy are a unique cultural force capable of exacting true and lasting change. From an art historical lens this work should be accepted as “art” because it’s unique (not to mention authenticated)—anything that advances the trajectory of art history is worthy of attention. But because of street art’s current standing—one foot in the commercial world, the other on the street instead of in museums like the rest of contemporary art—Banksy’s work tends to be covered from a solely commercial viewpoint. But we need to get over our infatuation of Banksy as a symbol of subversion and ask if his subversion is successful, or if it just continues the cycle it pretends to disrupt.

“Art is either plagiarism or revolution.”

—Marcel Duchamp

I. Performance, intervention, & spectacle: Reimagining “mixed media”

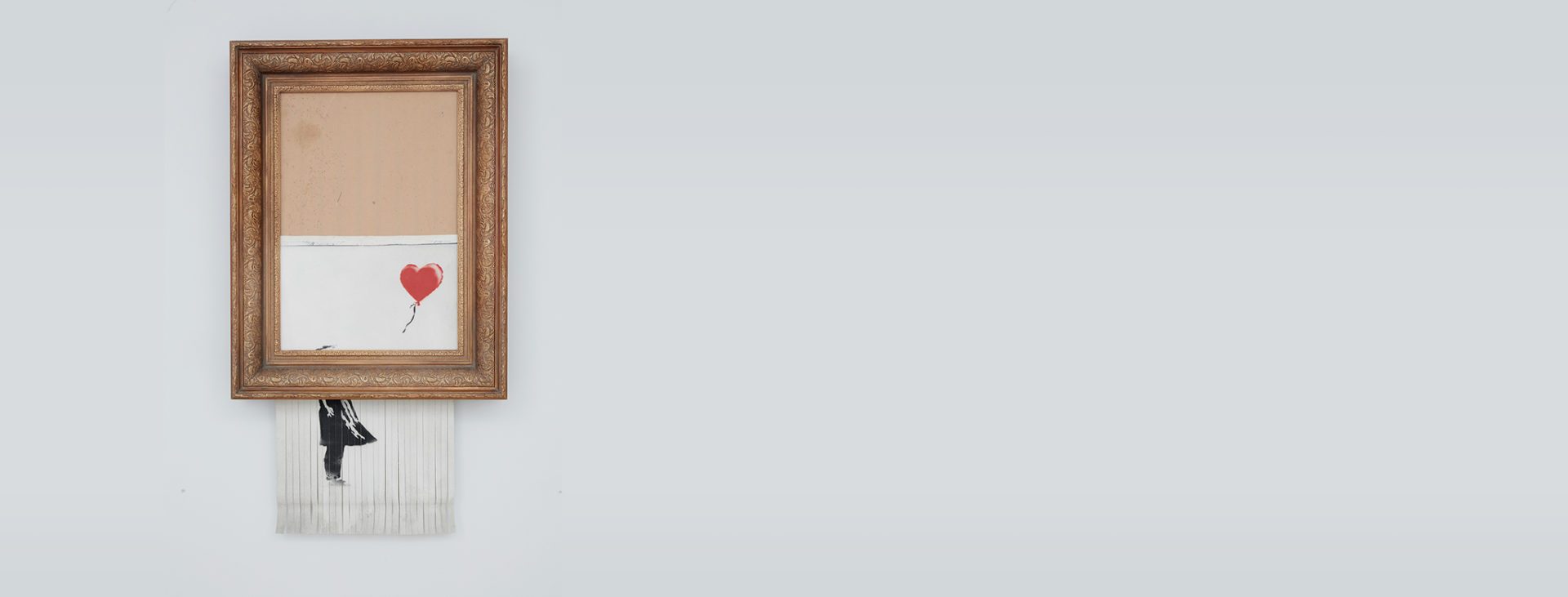

Before we can get into questions of whether this artwork is successful in its subversion, we should recognize its success as an artwork in and of itself. As twenty-first century artworks tend toward the temporal and experiential—fleeting moments of interaction that are thought to stay with viewers more, Love is in the Bin combines this performative element with the digital spectacle, still yet leaving a physical footprint behind, evidence of a crime committed.

A crime against himself through a rejection of commercialization, there’s no denying it’s a powerful statement. In the same way Marcel Duchamp tested the definitions of “art” by submitting R. Mutt’s Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists and that statement itself became the artwork, here Love is in the Bin is a performance of humiliation—a prank as artwork done on camera and in public with the intention of spreading around the globe at lightening speed. And a performative intervention becomes a spectacle.

Of course, there are few people alive in the world that have the platform Banksy has, so the privilege he enjoys and its contribution to the success of this artwork has to be acknowledged. But the way Banksy covertly shares and illuminates his work baits the media into giving him the attention that makes the work itself successful.

It’s also a kind of private performance, later made public: in his videos Banksy reveals a hand in the auction room pressing a button to initiate the shredding. Whether that’s his hand or another’s isn’t consequential. In the art world the super-successful get to establish “studios,” employing armies of people to bring their ideas into existence, and at the end of the day there’s only one name attached. (Although I hold hope that “Banksy” one day reveals “himself” to be a collective, setting street art apart from the rest of the contemporary art world in solidarity with the people who actually do the work.)

Lynn Hershman Leeson walked around the Bay Area as her alter ego, Roberta, in the ’70s and the evidence of those performances is collected by the SFMOMA. Marina Abramović puts herself through excruciating physical pain in front of an audience and she’s the icon of performance art. When Banksy destroys his own work, that act is informed by the very art world he supposedly rejects.

Still, Love is in the Bin takes all these threads and ties them together in a way that’s uniquely Banksy—blending intervention, spectacle, and performance in an act of subversion that itself is an artwork. There’s no evidence that Duchamp intended to ridicule the art world with Fountain—the fact that he went on to make “readymades” a significant part of his work suggests the exact opposite. In this way, Love in the Bin gives us something new: a prank, a statement, an act of destruction seemingly at another’s expense—at an entity that “deserves it”—creates a space for the art world to recognize and accept a subversive act as “art.”1

II. £300,000 a “fair price”

Through his videos, Banksy makes the intention of this work clear: No one but the artist controls his work. Sotheby’s attempts to define, attribute value to, and ultimately sell Banksy’s work are a ridiculous enterprise trafficking in the consumption of culture by the upper class. In the video the artist released three days ago, which showed a test shredding completing successfully (without stopping halfway like it did at the October 5 auction), the artist begins with footage of a Sotheby’s representative talking up the piece ahead of the auction.

He says the artist insisted on the frame as an integral part of the work because of his proclivity for the “romanticism,” his desire for an “ornate, National Gallery-esque frame.” I think it’s safe to assume by the inclusion of this quote in the video that Banksy thinks this is a hilarious pile of horse shit. The Sotheby’s curator says he thinks this is a “fair price” as the camera zooms in on the placard’s estimate of £200,000-£300,000 pounds, and then the greatest moment of irony comes: the Sotheby’s rep says, “That’s the fun of auctions, everyone’s got a chance.”

While technically true, this statement is powerful evidence of the wealthy (and those who cater to them) and their outright ignorance of “everyone.” If it takes an extra £300,000 lying around, then no, not everyone has a chance. But of course, to Sotheby’s, those who do are the only people who count.

Rich people in shiny clothes laugh and inhale hors d’oeuvres before soaking up the drama invoked by the auctioneer as he creepily smiles with each new bid. This gross consumption of culture by the upper class is what Banksy’s trying to expose through this work, but through the act he ends up enabling the sale he “thwarted.” The piece ends up selling for 247% over the highest estimate: £1,042,000, or nearly $1.4 million. The anonymous European woman who bought the piece said in a statement, “At first I was shocked, but I realized I would end up with my own piece of art history.” Likewise, Sotheby’s head of contemporary art, Alex Branczik, praised the piece as “the first artwork in history to have been created live during an auction.”

It’s been pointed out by people smarter than me, but Banksy’s lucrative new artwork was not a successful subversion of the system he critiques, instead he played into the hand he was pretending to steal from.

III. Who benefits?

First, Banksy’s act was in itself exclusionary. Only the wealthy got to be in the room to witness the piece be half-shredded. Even if they were being mocked by the artist, you had to exist in a certain income bracket or have certain connections to be there when art history was “being made.”

The provenance for the work states that the piece was “Acquired directly from the artist by the present owner in 2006.” In one of his videos, Banksy reveals the shredder was included in the piece in case the work ever went to auction—this was always the plan. (Although Banksy’s videos of the shredder’s internal workings seem a little too high-res to have been filmed pre-2006, which would mean the “owner” who put the piece up for auction was either in on the stunt or could have been the artist himself.)

But was the act of re-authenticating the shredded work as a performance piece a means of legitimizing subversion-as-art, or was it a way to placate Sotheby’s and evade liability for the stunt? (Onlookers did report seeing a member of Banksy’s team with a device in his hand being detained by security when he tried to leave.) Is exposing the consumption of culture by the wealthy doing anything to curtail it? Because I love art but the Earth literally does not have time for more conceptual art movements. Those who make something their cause on canvas or concrete, or through performance, need to answer for how they advance those “beliefs” in other areas of their lives.

I fully believe in an artist’s right to remain anonymous, but if Banksy truly cared about the causes his work speaks on behalf of, furthering his own brand wouldn’t always be the number one priority (which it pretty clearly is). He donated one street artwork (via authentication in 2014) to a local youth club in the UK and has sponsored free admission to museums when his own work is inside, but Swoon has pioneered sustainable building projects in Haiti and Stik authenticates street artwork consistently when the sale benefits a community directly.

Perhaps the persona of “Banksy” himself is intended as a hypocritical farce; an idea I particularly like because I think we’ve had about enough white, male (assuming straight?) geniuses. Perhaps Banksy is funneling more money than we realize back into the communities that made him famous, he just does it anonymously like his artwork. Maybe he just really doesn’t care that “love is in the bin,” or maybe Banksy’s a fatalist and doesn’t think there’s anything that can make the world a more equitable place by any broad measure. But his life is certainly different now from when he was growing up, and at the very least there are kids like him he could be helping more.

Seeing all the hysteria online about Love in the Bin, and witnessing how little civic or moral analysis of this work was happening in real time was disappointing to say the least. The only analytical texts being published by the art world media seem solely concerned with questions of “Is it worth more now?”—and that should be the opposite of the point. Instead we should ask whether Banksy truly means what he says through the work. If you’ve created something more valuable through the act of destruction, did you really destroy anything at all? Or are you just a fraud taking advantage of a system you willingly help perpetuate?

1. I am by no means suggesting that Banksy invented the subversive act as artwork. Street art’s brandalism movement existed long before we all knew his name. I’m just observing that because Banksy operates partly inside the systems he critiques, this is one of the first instances we’ve seen where the evidence of a subversive act becomes a commercially collectible entity.

Indeed, a Sotheby’s spokesperson told the BBC, “The new narrative is that Banksy did not destroy a work on its premises, he created one, adding value not detracting…It is a different work to the one that appeared in the catalogue, but nonetheless it is an intentional work of art, not a destroyed painting.”