An introductory note: The following is my artist statement, submitted as part of my PhD application in the winter of 2020 to the Institute of Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts. Now that I’ve successfully completed my first semester (😅), I’d like to share this text with you all here in an attempt to better contextualize the work I’m doing online through the Arrow, through ArtAround, and through my research and art-mapping practices. I’ve paired the text with photos of the collaborative public art spaces I’ve documented across Brooklyn and Manhattan, as these encounters have to me, proven the necessity of shared spaces of public visual expression.

After twisting in conceptual tangles of my own making for the better part of the past decade, the path of my practice as a scholar has finally become clear: a continual search for what could be conceived of as the “democratization of art”—not in a way that considers art as an affordable consumer item, but a theory that refers to the envisioning of a true and full connection between art and community. This requires breaking art from its frame, its status, and most importantly, dividing it from the very notion of ownership, something I’ve come to believe can only be made possible through a redefinition of public space. A formulation of this nature demands an unpacking of the concepts of ownership, public space, and community, tracing back their philosophical foundations and larger social understandings. This research into how art might truly be able to belong to a community, and a community to it, has been hampered by the cultural clinginess of “ownership” within our hyper-capitalist landscape. The many forms of privatization undertaken and manipulated by even our most sacred public art institutions has descended a fog of cynicism, disinterest, and in some cases even outright exclusion and oppression as it relates to art and our communities.

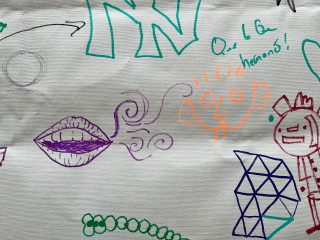

Photos taken August 8, 2018 on Troutman St. between Wyckoff and Irving Ave.s in Brooklyn.

But the converging legacies of détournement, subtervising, protest imagery (both material and documentary), street art, and graffiti—even the histories of Constructivism, Fluxus, and conceptualism—have created the imaginary space that can, and I’d argue in some ways already has, allowed for this redefinition and reclamation of public space as truly belonging to the people who live within it. Some examples of this shift in thought can be found in:

- the arbitrary and often problematic “elevation” found in the manufactured distinction between “graffiti” and “street art,” in which some illegally created work is christened as “art,” allowed to stay and in some cases even protected, coveted, or sold;

- the building of community coalitions and mural festivals with real and valued collaboration with local artists;

- and the creation of what are sometimes referred to as “free walls” where all members of the public are invited to contribute to a collective wall or three-dimensional space preserved for public, if temporary physical visual expressions.

My inquiry functions as two interrelated and interdependent phases: a phase of theory followed by a phase of research which in turn informs a constantly redefining theory, as our understandings of the terms “democratic” and “art” continue to shift and change. In a society in which art is truly democratized, all are endowed with the sense that we define art for ourselves, and that we all exist as artists in our own ways. An internalization coupled with an externalization of this notion of freeing “art” from the “art world,” as a detachment of art from its objecthood through ownership brings about a subsequent reimagining of “artist”—breaking art from its frame, its pedestal, from the walls that both protect and separate it from the public allows for a reimagining of who can put it there in the first place. In a society of democratized art, there are public spaces reserved and accessible 24/7 for community mural projects and what might be called street art or graffiti; and “vandalism” laws recognize the constant renegotiation of public space and the inherent inequality often found between “owner” and “vandal,” seeking restorative justice on behalf of all parties involved, while providing pathways for creative expression. How can the above examples of emergence into this space of inquiry be extended so that if we, if anyone, has something to say visually, there exists the space to say it in a physical way—an acknowledgement of our shared human need for the tangible as we wither within commodified digital ethers that provide as much connection as division sown.

The first phase, the theory, is where I currently exist. I posit that a democratization of art requires not only a re-envisioning of public space as public canvas, but a full-scale reimagining of the definition and purpose of public space in which ownership is collectivized instead of privatized. The extended research phase to follow will analyze examples of explicitly attempted “democratic” public art projects, for instance Monument Lab in Philadelphia and the “free spray walls” throughout Portugal, to determine how well these initiatives succeed in connecting communities and art, and to what extent they create the space for a public reimagining of the “artist” not as someone special over there but as someone special within.

I believe art’s power lies in its ability to connect us, and it’s this ongoing separation between art and community, maintained through the facade of “expertise” as exclusion, that my work aims to remedy. The MoMA holds just as much inspiration as Melbourne’s Hosier Lane. Visual art has endless potentialities and while everyone feels the right to have a favorite musical artist, the same interest or engagement within the public consciousness doesn’t exist for visual artists—and that is the fault of art institutions that continue to thrive and survive on exclusion. I’m not interested in which artist set an auction record, sold out a show, or got featured in Artforum, but I am very interested in artists whose practice centers community and connectedness, in whatever form that takes.

All of this leads me to my ultimate question, which takes the form of multiple versions of the same question—the most present to me being, “How does our art represent us?” followed by, “When has our art represented us?” in which “art” refers to those visual expressions that belong to all of us (those which exist in the public space), and “us” refers to the community living and working around the physical, material artwork, ever-extending outward according to geographic locality. I want to study the essential connectedness—or disconnectedness—between art and community, ultimately to identify methods and strategies that might allow for their coalescence.

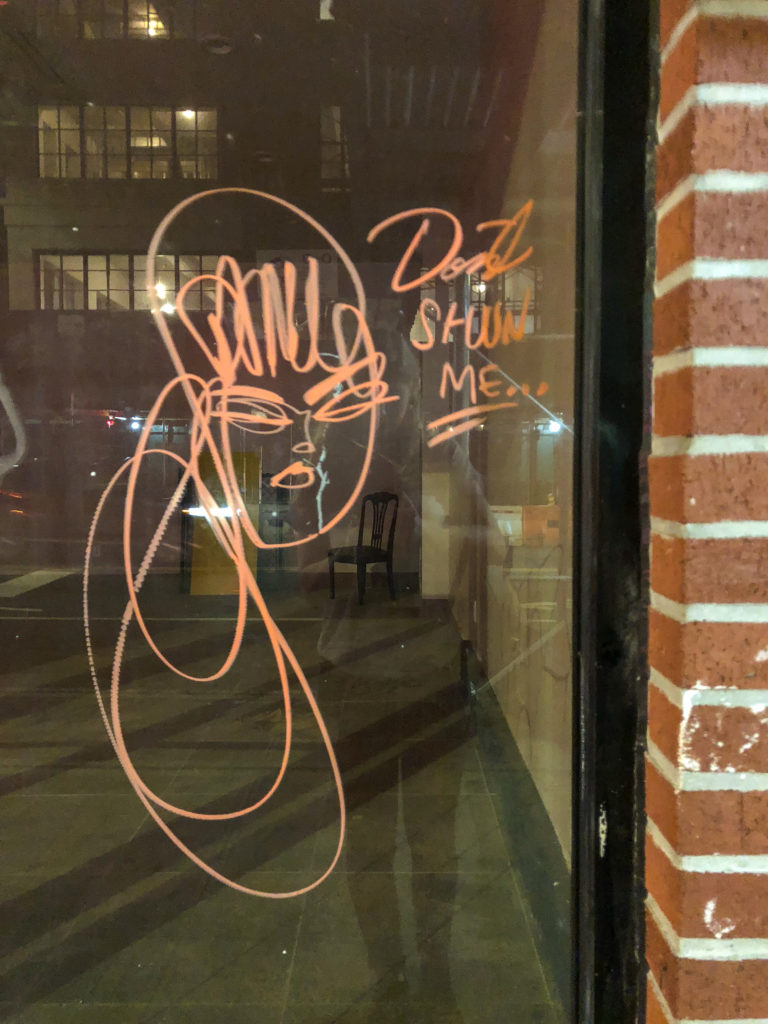

Cover photo taken on May 31, 2019 at Rivington and Ludlow Streets in New York.