The summer before I started eighth grade, my family moved from a suburb of Hollywood, Florida to Fairhope, Alabama — and on my school calendar, Martin Luther King Jr. Day suddenly become M.L.K. / Robert E. Lee Day. I was a little confused, because didn’t these two historical figures stand in direct opposition to one another? Also, wasn’t this new guy technically a traitor? I could sense, but couldn’t name, the cognitive dissonance between “all are created equal” and the white faces that filled the white spaces I found myself in when we moved to the Deep South in 2004. To be sure, it’d been mostly white faces and friends around me growing up outside the cities of Worcester, Pittsburgh, and Los Angeles, but in Florida, where we’d lived in the suburbs of Hollywood and Miami, our churches, schools, and neighborhoods were filled with people from different backgrounds who spoke different languages. When we moved to Alabama, I missed feeling different from those around me. I didn’t want to be surrounded by people who had the same exact backgrounds and beliefs, because how else could I keep learning?

I hadn’t yet realized how many of the statues around me celebrated Lee and his band of betrayers. As Lindsey Davis, I hated that I shared a last name with the president of the Confederacy. And in tenth grade, when I was taught that the Civil War was about states’ rights and not about slavery because slavery “actually wasn’t that bad” (which was very different from what I’d been taught at earlier grade levels in other states), I looked around my segregated high school and realized a lot of people thought that the South won the war—or at least that they didn’t lose it in the South. The worst part was, in a lot of ways, those people were and still are right. White supremacy reigns on, as different methods and levels of dehumanization developed that allowed us to assure ourselves and our fellow white people that we are, and always will be, more apt to lead, govern, decide, control.

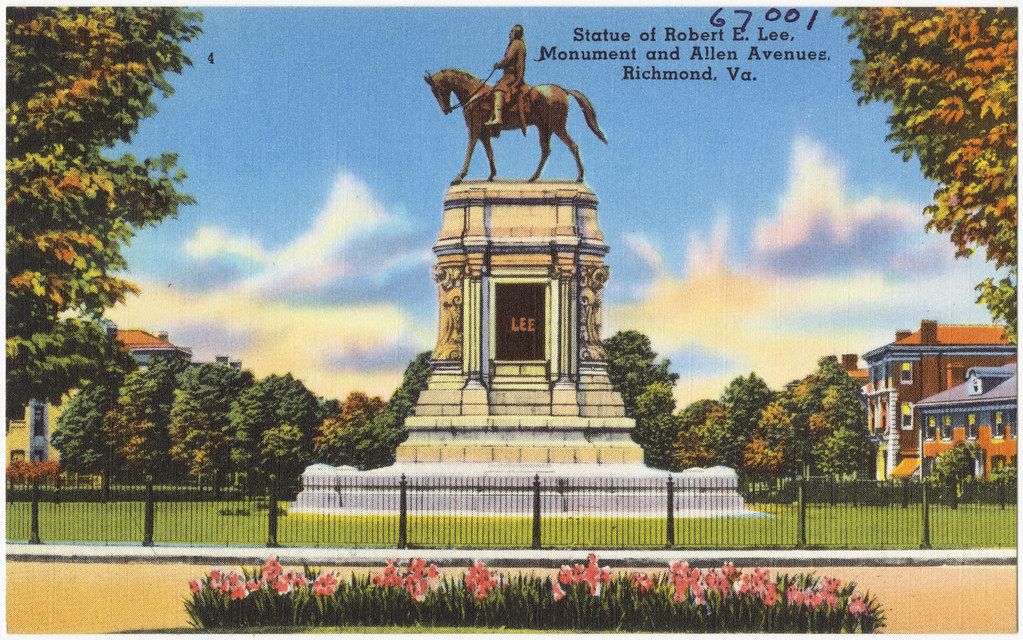

“Statue of Robert E. Lee, Monument and Allen avenues, Richmond, Va.” by Boston Public Library is licensed under CC BY 2.0

White people tend to be very selective in our storytelling. Historically speaking, we’re quite concerned about our branding. We don’t even mention, much less acknowledge the other demographics of the population with whom we share stolen land—those who have suffered for hundreds of years, and continue to suffer, at the hands of America’s deeply entrenched white supremacy. The existence of expensive bronze statues situated high above public spaces that serve to memorialize those who fought to keep people of color enslaved proves that this legacy exists. And the debates about these monuments that we’re still having to this day—the people who think a heritage of hate and subjugation is one worth celebrating—prove the legacy of white supremacy is ongoing. (In April, a woman in North Carolina had her home terrorized after she advocated for the removal of a Confederate monument from outside her local county courthouse, where it not only still exists but was rededicated in 2006.) As I’m writing this, I know I’ll have immediate family members who will disagree with the ideas I’m sharing here, and that also, will represent a continuation of white supremacist thinking.

Our framing of things and the language we use determines how—and how well—we understand. The Civil War is often talked about as “the North versus the South,” but that phrasing doesn’t accurately reflect what happened. It was the United States of America versus a treasonous Confederacy—not a nation divided, but a nation in which a group of powerful men saw their wealth and status as more important than the health—indeed, even the existence of—the nation. They were the opposite of patriots, and the monuments that honor them in all public spaces throughout the United States must come down.

“Monument Blvd RVA” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Monument Blvd RVA” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Robert E. Lee Monument” by joseph a is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“Robert E. Lee Monument” by joseph a is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“RVA 2020 MDPC” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“RVA 2020 MDPC” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Lee’s Final Days” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Lee’s Final Days” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The 2020 evolution of the Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, VA.

In a country that truly believes in “equality under the law,” monuments celebrating those whose lives and legacies represent the antithesis of that ideal do not belong. They simply don’t make sense in an America that’s working to move away from white supremacy as a guiding ideology. Monuments in themselves imply power, and these Confederate statues only work to legitimize and extend the insidious “lost cause” narrative that comforts white people, allowing them to paradoxically believe in both “democracy” but also that it makes sense for white men to disproportionately represent us in government because they’re the most “fit to lead.”

In a United States of America that truly believes in “equality under the law,” monuments celebrating those whose lives and legacies represent the antithesis of this ideal do not belong.

The removal of the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia on July 10, 2021 was an incredible, historic moment in the American public landscape—especially in light of the explicit white supremacy demonstrated by the Unite the Right rally that mobilized around that bronzed badge of tyranny almost four years earlier. To have monuments celebrating traitors elevated on plinths and columns says that we think they deserve to be up there. They don’t. No one should look up to Robert E. Lee—not physically and not metaphorically.

When I say these monuments “must come down,” I think each community should decide collectively how they want to bring their Confederate monuments down. Removal is one option, removal and replacement is another. But some communities might feel that these actions are too revisionist and want to contextualize the monuments in some other way, through counter-sculptural works or installations. At a minimum these monuments need to be brought down to ground level, as an acknowledgement of this incredibly late reckoning that we’re finally having with America’s founding hypocrisy.

“Lee Removal” by skooksie is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

If America is great, it’s only because of our capacity to change. Because of the amendments, revisions, removals, and remaking of our laws and systems that are optimistically intended to be constantly improving the lives of all Americans, striving towards the ideals we say we stand for. The threads of Civil War’s “lost cause” mythology—furthered by the very existence of these monuments—can be traced forward in time, to some of the deepest fractures in our country today: the unwillingness to accept the results of the 2020 presidential race (following the election, fully four in ten Americans—almost half of us—believed Biden was not the fair winner); the related violent insurrection at the Capitol on January 6 and the refusal to acknowledge or accept the severity of those domestic terror groups that misappropriate the language of the Constitution in calling themselves “militias”; the continued barrage of efforts by Republicans at all levels of government to make voting more difficult in general but especially in non-white districts, in the face of zero evidence of “voter fraud” and after generations of Americans protested, fought, and died for the idea that access to the ballot be free and fair.

Confederate monuments have a direct tie to these voter suppression efforts. Every bronzed racist represents a continuation of the entrenched belief that white people are smarter, better, more capable, different. They create a space in which white people feel safe wondering “Should their vote count as much as mine?” In direct defiance of democracy, each Confederate monument that remains on its plinth or high on its column tells us no. Each standing Confederate monument says that “real” Americans are white.

Each standing Confederate monument says that “real” Americans are white.

In a true democracy, the public landscape should be collectively oriented, not “separate but equal,” not “above” and “below,” but together, as a celebration of what makes each of us so different. For the collective imagining of “statue” to equal “white guy on a horse” says so much about the current function and purpose of art—that it continues to exist in its historical capacity as a means of maintaining, establishing, and enforcing white power.

“RVA 2020 MDPC” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

To learn more about voter suppression, the Brennan Center for Justice is a great resource.

Header image: Erin Edgerton/The Daily Progress via AP.