So I tried to make that happen, but like a lot of first attempts I messed it up. I started by trying to photograph all the art myself, somehow under the impression that the deep well of already perfectly good resources wouldn’t be open to collaborating until I proved I could build something valuable too. But people—and I’ve found especially people in the arts—are nice, and last year I started asking street art festivals to let me archive the data on their murals that already exists, and so far, every single one has shared their collections with me (and therefore, I like to think, us).

What did I learn spending two years documenting the art on the streets of San Francisco? That it was a perspective, my perspective, and one I hope remained as impartial as possible—but it was definitely not the most effective way to build an archive of all the different artworks that are already being excellently documented by existing sites (I’m looking at you, Street Art SF and the Clarion Alley Mural Project!). Even if they’d only be willing to share a third of their archives, it’d still have been a hell of a lot more artwork location information than I could create by hand in months.

“What did I learn spending two years documenting the art on the streets of San Francisco? That it was a perspective, my perspective, and one I hope remained as impartial as possible—but it was definitely not the most effective way to build an archive…”

Now that I know that all you have to do is ask (and that it’s actually pretty simple to aggregate location data from embedded Google Maps), I’m pivoting. I did find some gems that I haven’t been able to find a shred of digital evidence of, but it really is so much work to find and photograph art that for the most part already exists online anyway. Some days, well a lot of days in San Francisco, it’s cloudy—and to truly represent these works in any significant way I’m going to have to reach out to the artists anyway. But I did build a snapshot in time of the art I was able to find in 2013 and 2014—534 works in total.

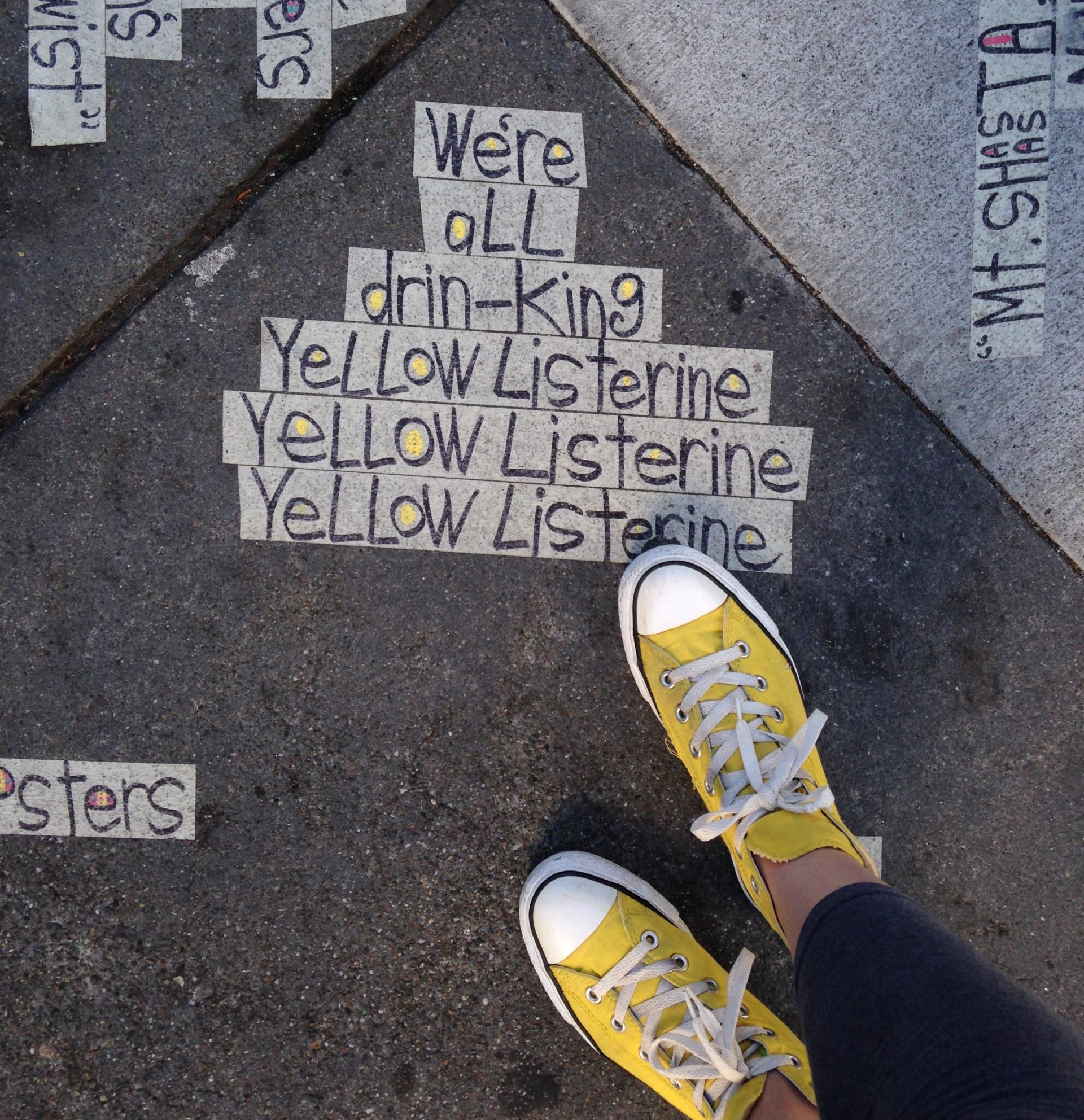

And besides realizing that it was definitely the most inefficient approach to what I hadn’t yet realized was ultimately my goal, sometime more recently I also realized that a part of me did it because I loved it—I still do it, everywhere I go. I hate selfies, I hate photos of food, but I cannot walk by a piece of street art, public art, or sometimes even weird urban peculiarities without taking a picture of it. And not to Instagram it (I think my failure there is pretty obvious), but to create some record of its existence—because I believe that all public creative visual expressions that took time and effort to create are a gift, and what those gifts are and how long they’re allowed to exist says a lot about how free a society truly is.

Sadly, expectedly, the U.S. is not doing so hot in this arena. The only things that even put us on the field are some city’s percent for art programs and POW! WOW!, and the growing number of incredible local arts festivals popping up around the country—everywhere from Fort Smith, AR to Richmond, VA. Plus of course, the entire nonprofit public arts sector. I geek out hard over even the existence of Creative Time, Public Art Fund, Mural Arts Philadelphia, and Living Walls. But still, since I first became obsessed with what I like to refer to as the art that belongs to all of us, I’ve noticed each year there’s another street art festival or public art initiative. And it’s my foremost mission on this earth to document and aggregate all the work they’re giving to the world, tracking its changes to create a record of how our plazas and intersections, and excitedly now even billboards, breathe as one creative expression follows, joins, or replaces the next.

So this text is the start. I’m reaching out because I know every single person in the world with a smartphone (and therefore most of the people reading this) has at least one photo of a mural or a sculpture or some funny quote on a wall somewhere, and it’s in a place accessible to everyone—that’s public art and it’s worth archiving.

Thanks to the magic of GPS-tagged photos, we are all collectively sitting on a goldmine of data on the art that belongs to all of us. And after many years (a lot of workarounds, and trial and error), I finally have a system capable of:

- individual uploads: for the one-off anonymous types

- a community-tracking system so that people with a lot of photos can get credit for and aggregate everything they’ve uploaded

- and what I’m pretty sure is the first-ever online, bulk-upload-capable aggregator of both street art and public art (although I know the Public Art Archive does import civic collections in bulk)

This is everything I could think of to accomplish what I actually set out to do six years ago in a new city that inspired me with its vibrance. The only catch is, I can’t do it alone and I realize now I never could. So I’m asking you—yes, YOU there reading this on what I assume is a tiny screen: On your phone, do you have precious documentation of public art, street art, or a funny thing you saw outside that you’re not sure is art but was so interesting you took a picture of it? Upload it. If you took the photo on your smartphone the location’s already in there and our system can grab it automatically.

Upload right away if you don’t care about tracking your submissions (you’ll still get credited for your photos of course!), or sign up with your real name, an alias, whatever you want, and get your own tag as a member of this art-tracking community I’m starting called the Ambassadors. Or if you or someone you know is involved in the creation of public art—as an artist, or through a nonprofit, city commission, or corporate collection—email me and let’s archive their work together.

If you’ve read all this, you definitely deserve what my title promised: What I *actually* learned documenting the art on the streets of San Francisco:

- It’s really hard to make art installed on a crooked street look straight in a photo.

Sometimes you have to sacrifice alignment to fit the whole wall in a single frame, and a lot of times that’s straight up impossible anyway—try taking a pano. - Download a super detailed weather app and check for things like visibility, cloud cover, and smart forecasts for landscape photography. I’d say 60% of the days during my two years in SF were shootable, 35-40% ideal.

- Clouds make for washed out colors. Color correct! Boost brightness and saturation, but not by too much (<+10).

- Some of the best art is in the most overlooked neighborhoods. Be polite and know that you’re a visitor. I made some friends but I’ve also been (literally) spat on and cursed at, so if being someone with a camera seems out of place, know that it is and be respectful and upfront about why you’re there. The easiest explanation I found was that I was documenting art for a “school project,” since the whole I’ve-dedicated-my-life-to-building-a-living-archive thing is kind of long-winded and most times people don’t care anyways—you can tell when they do.

- Any anonymous artwork that was done before 2009 (or whenever Google Street View first rolled through your neighborhood) is super hard to find evidence of online if the artist didn’t sign it. I tag those as a “mystery artwork” and ask Instagram.

Think of it like a scavenger hunt, and embark on your own art adventure while simultaneously helping preserve the art in your community through documentation. Sign up or email me and let’s build something of value together 🙂